The Landing hotel in Ketchikan is flooded with charter fishermen and other tourists this time of year, which makes it one of the town’s busier places to stay.

But right now the The Landing is hosting a different sort of visitor. And her story is part of a medical trend that has made Alaska the best in the nation in an unlikely area.

Kelli Taylor is 24 years old and 37 weeks pregnant.

Her previous pregnancy was complicated, so her doctors are taking a few extra precautions, but other than that she seems pretty…. normal, with a healthy sense of humor about the sights she’s seen in Ketchikan.

“We’ve walked around the mall a couple times, the greatest mall in Alaska,” Kelli says, sarcastically. “There’s a Walmart here!”

But there is something unconventional about Kelli’s situation. She’s from Klawock, on Prince of Wales Island. That’s about 70 miles from Ketchikan.

The medical center in Ketchikan is the closest facility equipped to deliver babies. And, as a policy, the women’s clinic in Ketchikan requires pregnant women from rural communities to be in town at least two weeks before their due date.

So, women like Kelli get on a ferry or floatplane while very pregnant to the city. And then, they wait. And wait.

“I’m definitely bored out of my mind, for sure,” Kelli says of her stay in Ketchikan.

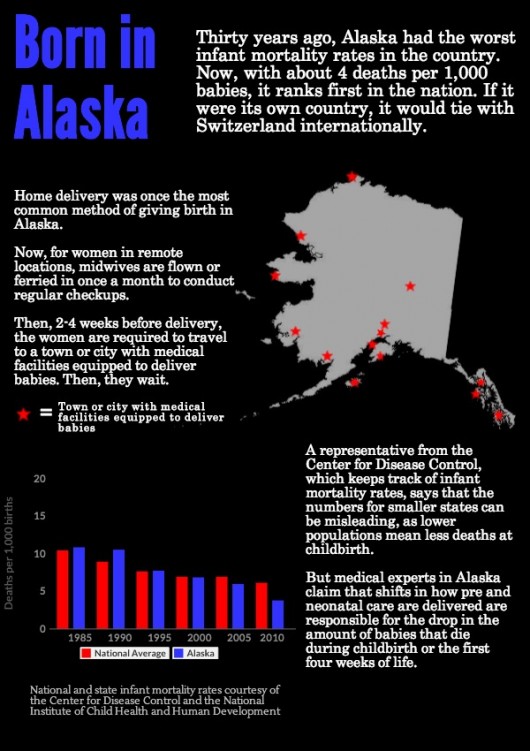

Despite Kelli’s boredom, her situation represents a radical transformation from what Alaska prenatal care was like 30 years ago. That change, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics, is responsible for a dramatic turn-around. Alaska used to have the worst infant and neonatal mortality rates in the nation. Now, it has the best.

If Alaska was its own country, it would tie Switzerland, and give Scandinavia a run for its money.

Representatives from Alaska medical advocacy groups say the state’s rise to the top is due in large part to advances in how care is provided in often remote locations.

Dr. Matt Hirschfeld has been on the front lines of that transformation at the Native Medical Center in Anchorage.

“Beginning in the early ‘80s, late ‘70s, people in Alaska realized there had to be a better way to deliver care to women so that they had more healthy babies,” Dr. Hirschfeld says. “There became a concerted effort between the Alaskan Tribal Health System, Providence Hospital and the state of Alaska to develop a system such that women had healthier babies when they were born.”

Medical centers in the state now use a mix of midwives and OB/GYN doctors to deliver that care; if the woman, such as Kelli, is in a remote town or village, midwives are flown or ferried in every month to conduct regular checkups. Then the medical center requires the women to travel, two to four weeks before their due date and wait for delivery.

Marta Poore has worked as a midwife with the Ketchikan Medical Center for nearly three decades and has seen this medical transformation firsthand. In her own words, medical care in some villages back then was akin to that in third world countries.

“I know one woman, I can still remember, it was a preterm twin pregnancy,” Poore says. “And they’re trying to prepare for a medevac, and she’s got her husband out there cutting down trees so they can clear a spot big enough for the helicopter to come in.”

Like everything in Southeast, aspects of the system that have developed are uniquely… well, Alaskan.

Representatives from the Ketchikan Medical Center say that more than half of those who come from out of town are Alaska Native.

At least seventy-five percent of the women are on Medicaid. That’s good for the patients, as the coverage pays for both their transportation to Ketchikan and much of the cost of their stay.

Even so, coming to Ketchikan can be costly. Kelli Taylor’s fiance, who works at a grocery store in Klawock, couldn’t afford to take the time off to stay with her. Kelli, who works in the same grocery store is obviously also not working while she’s in Ketchikan.

“It’s really expensive to be over here for a month,” she says. “I’m not working, I had to take time off work to be over here because that’s what the doctors recommended. If it were up to me I’d be at home, and fly over if my water broke or something.”

Kelli’s mother is spending the full three weeks with her though, at a cost of at least $200. And although Medicaid covers some food costs, the voucher can only be used in The Landing’s restaurant.

The boredom and costs can be so great for the women, the midwife Marta Poore says a unique phenomenon develops.

“There’s a lot of pressure to induce. Especially when you’ve got two or three kids on the other island,” Poore says. “Somebody is watching them, but you want those kids (with you), because you’re here all by yourself, your husband needs to work as far as logging or fishing or whatever he’s doing. And then you may find the woman here all by herself, and she is depressed. And then the husband comes in for the weekend and you want that baby, now.”

Of course, the doctors and midwives can’t ethically do much to help the women deliver early, beyond recommending spicy foods or walking.

Kelli’s mother, who has delivered three babies this way in Ketchikan, understands her daughter’s situation. And now that the younger woman is going through it, they agree:

“If you pretty much talk to much anyone who’s gone through it, it’s worst part of being pregnant, coming over to Ketchikan to wait,” Kelli says, with her mother nodding in agreement.

Kelli says that if given the option, she’d choose to give birth at home, even though it would be higher risk.

Doctor Matt Hirschfeld works at the Native Medical Center in Anchorage. He has been at the forefront of Alaska’s prenantal success story, and says he is happy with how care in the state has progressed.

But, he admits, there is still room for improvement, especially in that almost-purgatorial wait period for the women before they give birth.

“There’s always room, the goal is to get this rate to a zero,” the doctor says. “We have these moms who are here in Anchorage or Bethel or Ketchikan for weeks before they deliver. And we really don’t do enough with that time. We have a captive audience we could really have some major effects on the pregnancy if we had a concerted effort towards education.”

And, he says, there may be some lessons for the rest of the United States in Alaska’s transformation.