Last year, the Legislature approves new regulations for cruise ships to release wastewater into Alaska’s oceans. Since then, the state has developed a permit process based on those regulations, and that permit process is now open for public comment. Alaska Department of Environmental Conservation’s Division of Water Director Michelle Hale stopped in Ketchikan on Wednesday to talk to the Chamber of Commerce about the permit process, and what the state is doing to protect Alaska’s environment.

With the new regulations in place, cruise ships that travel through Alaska’s Inside Passage will have better wastewater treatment systems than some coastal communities.

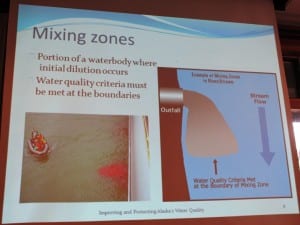

Hale said no untreated sewage is allowed to be dumped, and the legislation closed so-called “donut holes,” parts of the ocean that were just outside of state jurisdiction. The main activity that the new regulations now allow is the use of mixing zones.

“And that’s very similar to all other industries and municipalities in the state of Alaska,” she said. “It’s a little bit controversial relative to cruise ships; it’s a very standard practice when we are actually permitting wastewater discharges.”

Ketchikan has numerous mixing zones for the various wastewater permits, allowing discharge into the Tongass Narrows. They include the City of Ketchikan’s Charcoal Point Wastewater Treatment Facility, Point Higgins School, seafood processors, the shipyard, the Coast Guard, Vallenar View Mobile Home Park and the airport, among many others.

Mixing zones allow discharge to exceed the standards for certain contaminants, as long as

the standards are met within a certain distance of that initial discharge. In other words, it becomes diluted fairly quickly after its hit the water.

Hale said mixing zones for cruise ships are a little different, because ships move.

“The cruise ship defines two different regulatory mixing zones, one for discharge underway and one for discharge at 6 knots or less or stationary,” she said. “Primarily, that 6 knots or less is for stationary vessels, but we kind of had to make a break point. So, if you’re going faster than 6 knots, you get covered under one mixing zone, if you’re going slower, you’re covered under another.”

Hale said some members of the public were concerned that the permits for cruise ships wouldn’t protect the ocean enough. But, she said, her division wrote the permits in a way that treats cruise ships like other wastewater discharge systems.

“When we do our modeling and establish limits, we do that so that the water is protected, so that water quality is protected for the uses that that water is used for,” she said.

Hale said the water must be safe enough for a fish to pass through the area within 15 minutes, and not be affected.

She notes that it’s possible for cruise ships to treat wastewater so that it meets all standards before the water is released into the ocean; but it’s not practicable.

“This is our regulatory definition for practicable: ‘Available and capable of being done, taking into consideration cost, technology that actually exists and logistics, in light of overall project purposes,’” she said. “So, what practicable means, is it has to make sense.”

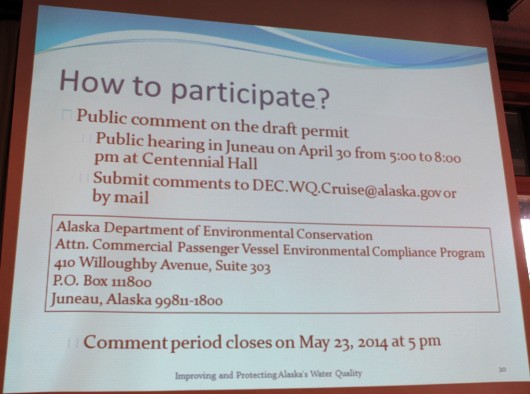

More details about the draft cruise ship wastewater permit program is available on the Division of Water’s website. That’s also the place to go to find out how to submit comments. The comment period closes May 23rd.

A link to review the Division of Water’s draft permit for cruise ship wastewater is below: http://dec.alaska.gov/water/cruise_ships/gp/2014dgp.html