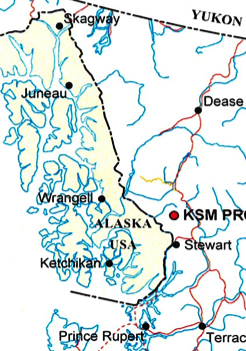

The KSM, Red Chris and Galore Creek projects are among several planned for northwest British Columbia, near the Alaska border. (Map courtesy Seabridge Gold)

Canadian investors are putting millions of new dollars into mining projects near the Southeast Alaska border. They include the KSM and Tulsequah Chief prospects, which critics say could damage regional fisheries.

KSM is a multi-metal deposit about 150 miles northeast of Ketchikan. It’s near rivers or their tributaries that drain into the ocean northeast of Ketchikan and just south of the Alaska-B.C. border.

A group of Canadian financial firms are in the process of purchasing a million shares of Seabridge Gold, KSM’s parent company. They have an option to buy more, with the total new investment between $13 million and $15 million.

That’s not a lot for a large mine. So Seabridge, headquartered in Toronto, is negotiating to find much larger investors.

“We continue to seek partners and we have confidentiality agreements with several,” says Brent Murphy, vice president of environmental affairs for Seabridge Gold.

Exploration continues at the KSM project, sometimes compared Western Alaska’s Pebble Prospect.

In an interview at a Vancouver, British Columbia, office, Murphy said the company has drilling rigs on site right now.Officials say the more-than-$5-billion project could be built and ready for operations by the end of the decade.

“We currently have about 35 to 40 people in camp and the drilling program will continue until the end of September,” he says.

Seabridge has numerous regulatory steps to complete. But officials say the more-than-$5-billion project could be built and ready for operations within five or six years.

Another near-border project is within a few months of completion.

The Red Chris Mine is already stockpiling copper and gold ore. The project, about 125 miles east of Juneau, is completing its onsite buildings, mill and tailings-storage system. It’s near the upper watershed of the Stikine River, which empties into the ocean near Petersburg and Wrangell.

Officials at its owner, Vancouver-based Imperial Metals, did not respond to repeated interview requests. But Imperial’s website says the $530 million project is expected to open within a few months.

Imperial Metals’ Red Chris Mine is close to opening. Camp housing is shown in this photo. (Courtesy Imperial Metals

Like most other near-border mines, development is being helped along by a transmission line to new hydroprojects in the province’s northwest.

“The ability to hook up to power is a very important part of development or any considerations for investment,” says Karina Brino, president of the Mining Association of British Columbia.

She says the line is part of a province-wide effort to boost mineral-extraction projects.

Another project in the Stikine watershed is the Galore Creek copper-gold mine.

Development has been suspended so co-owner NovaGold can focus on its Donlin Creek project in Western Alaska.

But Communications Vice President Mélanie Hennessey says exploration continues. During an interview in her Vancouver office, she said the corporation is reviewing drilling and other work conducted during the past two summers.

“It involves quite a bit of work, quite a bit of technical work on modeling. And so it’s more desktop work than it is physical, onsite work,” Hennessey says.

Identifying more ore would allow NovaGold and co-owner Teck Resources, also Vancouver-based, to find new investors.

“We do have a process underway to looking at selling a portion of our interest or our full interest in the asset,” she says.

Another near-border project is the Tulsequah Chief Mine, which Chieftain Metals Corp. is trying to reopen. It’s on a tributary of the Taku River, which ends near Juneau.

Toronto-based Chieftain recently announced it had acquired a nearly $20 million loan to look for ways to lower construction and operational costs.

Those and other mines have raised numerous concerns with Southeast Alaska environmental, fisheries and tribal organizations.

“It’s going to create a lot of acid-generating waste rock,” says Guy Archibald, mining and clean water program manager for the Southeast Alaska Conservation Council.

He says that acidic water can disrupt transboundary rivers, and those nearby.

“It can have very significant impacts, starting with the fisheries. And that leads to problems with the economy, which leads to issues in the small communities, whether they can continue to maintain their populations,” Archibald says.

The group Rivers Without Borders is also highly critical of the projects’ impacts.

Several other mine projects are being explored or developed in the near-border region.

One is Schaft Creek, a copper, molybdenum and gold mine owned by Calgary, Alberta-based Copper Fox Metals and Vancouver’s Teck Resources. It’s in the Stikine River watershed, about 150 miles northeast of Petersburg.

Copper Fox says this summer’s work includes a series of studies aimed at finding more ore and reducing construction and mining costs.

(This report is one in an ongoing series on mines that could affect transboundary rivers flowing into Alaska and nearby waters.)