It’s seven o’clock on a Saturday morning. I’m in a warehouse off the main runway at the Ketchikan International Airport. The trucks, plows, hoses and other airport equipment have been moved, and there’s a pile of headless, handless, footless dummies on the cement floor.

It’s seven o’clock on a Saturday morning. I’m in a warehouse off the main runway at the Ketchikan International Airport. The trucks, plows, hoses and other airport equipment have been moved, and there’s a pile of headless, handless, footless dummies on the cement floor.

The airport is putting on an emergency drill to test the community’s response to a simulated plane crash. I’m one of a few dozen people who have volunteered to be victims. Most of the victims are students from the high school and middle school. They get class credit for community service. But to be honest, most of them are here for the make-up.

There’s a team of make-up artists, and they have tubs of flesh-colored putty and bruise-colored make-up for the exercise. For fake blood, they use peanut butter dyed red. The line for serious wounds is significantly longer than the minor wounds line.

There’s a wide range of injuries: bloody noses, deep gashes, internal bleeding, severe shock, contusions, head trauma. There are even two high school seniors playing pregnant women in shock-induced labor, and a severed arm.

“What’d you guys get? – Lame. I got something in my leg. I got a spine injury and diarrhea and vomiting, because I think I can simulate that. She’s got a stick in her head. Ouch…”

Preparing the wounds takes almost two hours. We sit, chat and eat while we wait. Around 9, Adam Archibald, the airport security coordinator who is directing the drill, gives us some instructions.

“When the responders are coming down to you play the part…”

We load up on a yellow school bus, and they take us down to a gravel parking lot below the runway. We wait. After some time, they tell all the people who can walk to get off the bus. With a leg wound, I limp outside.

We load up on a yellow school bus, and they take us down to a gravel parking lot below the runway. We wait. After some time, they tell all the people who can walk to get off the bus. With a leg wound, I limp outside.

It takes a few minutes for the first responders to get there. The airport fire truck is first on the scene, and several fire fighters wearing silver suits and gas masks get out and unravel a hose. They squirt down the bus with foamy white fire-retardant. The mobile victims outside limp and laugh away from the spray.

We’re directed up the hill, back to the warehouse where the donuts, banana bread and coffee are located. We hang out for a while, waiting for more responders to come to us. Our injuries are less serious, and we are second priority.

“The thought is that if you’re able to get up and walk and get all the way up here, you’re going to be OK for a little while longer.”

After a while, EMS come.

I have a penetrating leg wound. There’s a piece of debris lodged in my leg below my knee – it’s actually a broken piece of a chopstick. The instructions I received direct me to express major complaints of pain on the scene and at the hospital. I take some creative liberties.

I have a penetrating leg wound. There’s a piece of debris lodged in my leg below my knee – it’s actually a broken piece of a chopstick. The instructions I received direct me to express major complaints of pain on the scene and at the hospital. I take some creative liberties.

“There was a plane crash, we had sushi on the plane. (You had sushi?) Yeah, with chopsticks and that’s why there’s a stick in my leg… Do you have medication in there?

A lot of creative liberty. I’m probably the whiniest victim in the entire drill.

“Please give me medication. Somebody give me something. I’m in so much pain. I can’t walk.”

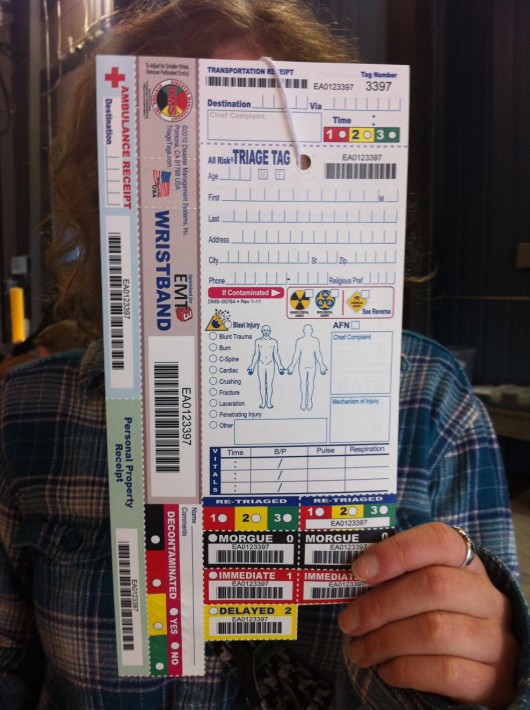

They strap me in a gurney and load me into the ambulance. I’m whisked to the hospital. I’m quickly processed in the emergency room and sent to surgery. I wait in the lobby among other victims. Our clothes are torn, cut open by medical scissors; our bruises are not fading, but our fake flesh wounds are falling off, and we all smell a little bit like peanut butter.

We’re given more snacks and water and told to sit for a while. We swap war stories. We rub off our make-up. We wonder what happened to the rest of the victims – who would have gotten airlifted to Seattle, who would still be at the airport, who would have been sent to the morgue. We sit quietly after a while.

There was more laughter than anything during the drill. Where there would have been pain, sobbing and hysteria in real life, there was play, singing and hilarity. A phrase repeated throughout the day was, “in real life…” In real life, we might not have been so patient.