From left are Merta Kiffer, Beth Antonsen, Margaret Antonsen, Delma Inman, Doug Vig, Joan Aegerter, Gail Alguire and moderator Alaire Stanton.

Victory gardens, USO dances, air raid drills and blackouts, and the forced internment of Japanese and Aleut Alaskans. Those memories and more were discussed last week by a group of Ketchikan pioneers who lived in Alaska’s First City during the 1940s.

The seniors were brought together for a forum organized by the University of Alaska Southeast Ketchikan Campus Library, and its ongoing AskUAS program.

World War II was the overriding event of the 1940s. The war started in 1939, but the United States didn’t get involved until two years later.

Margaret Antonsen remembers exactly where she was on Dec. 7th, 1941.

“I was in Dr. McKenzie’s dentist office, getting my teeth worked on,” she said. “He was in the

second story above the then-First National Bank, and we were standing in the window, waving our hands and everybody was screaming and yelling down on the streets. Nobody could believe what was happening.”

What happened was that Japanese fighters bombed Pearl Harbor, an event that pushed the United States into the war.

And, as Merta Kiffer pointed out, there wasn’t much dissent among Americans.

“One thing about that war, we were all in it together. There was not all this division,” she said. “Everybody was in it. Of course, we were attacked first, so we all felt the same about it.”

Part of that could have stemmed from the sheer numbers of Americans who served in World War II. Doug Vig said that included more than 800 from southern Southeast Alaska alone, which means many of the men were gone.

“Everything fell to the women, especially if they were married,” he said. “Everybody grew a victory garden, and grew all sorts of vegetables.”

Victory gardens were important nationwide because food was strictly rationed to support the war effort. Alaska wasn’t technically rationed, because it was still a territory then, but food still was scarce. The gardens helped, but there was a shortage of some items, such as butter and milk.

The seniors remembered the early version of margarine, which was white and came with a special dye pack that you mixed in to make it yellow; and powdered milk called Klem, which turned them all off milk.

While many of the community’s men were off fighting the war, there were servicemen stationed in the area, including over on Annette Island, where the main airport was at that time.

Gail Alguire remembers a story about a couple of those servicemen coming over to Ketchikan for a night of drinking. They ended up putting the whole town on high alert. At a certain point in their evening, she said, they decided to climb Deer Mountain in the dark. They did make it to the top, but then: “They had a kerosene lantern with them, and it tipped over and the cabin caught fire and it burned,” she said. “Everybody in town thought the Japanese had landed, and it was a signal fire signaling where they would land to take this town.”

While an amusing story now, there was a real concern about attacks, especially after Japanese fighters bombed parts of the Aleutians. That led to the evacuation and internment of Aleut Natives, some of whom were brought to Ketchikan.

Delma Inman remembers that the Aleuts were housed in Quonset huts at Ward Lake.

“My mother was one of the ones that started collecting supplies, food, pots and pans, clothes, from the different churches in town. So, my dad would drive them out in the school bus,” she said. “I got acquainted with a lot of the Aleut kids and went to school with some of them. They had a tough time out there, because they weren’t used to this part of the country.”

The official explanation was that the Aleuts were moved for their own safety, but the lack of planning and poor conditions of the facilities used for those evacuees led to a high death rate.

Inman also recalled when Ketchikan’s Japanese families were taken to internment camps in the Lower 48. She noted that her family moved in to the Tatsuda’s grocery store to take care of the building after that family was taken, at gunpoint.

In the audience was Bill Tatsuda, who was born after the war but who has heard the stories about that time from family members.

“When they got short notice to leave town, when they got put on ships, Pete Johnson was one of the guards, he had to hold a rifle and follow them around,” he said. “But, listening to my uncles talk about it, they were all making fun of him and laughing. Because he had to guard his friends, basically.”

Tatsuda said his uncles fought for the U.S. during that war, and one was wounded three times in Italy.

One incident many of the panelists recalled clearly was the day the Canadian steamship Prince George burned at Ketchikan’s Heckman Dock. That was September of 1945, and Gail Alguire said her family was due to leave on that ship on that day.

“Just as Mother called the taxi to go to the boat, the fire alarm sounded,” she said.

They ended up flying instead.

Joan Aegerter remembers that the burned-out hulk was eventually taken to the back side of Pennock Island, and a group of friends decided to have a little adventure. They boated over to the nearby island, then looked for a way to get into the George.

“It was difficult getting on board, because the tides weren’t so that we could get up to the place to get into a porthole, but we finally did, and we got onto it and marched around,” she said. “We were on the floor where the kitchens were, and there sitting on big trays were muffins, just as beautiful as you would imagine muffins to be, but really just charcoal.”

Aegerter said getting back off the Prince George was even more challenging, because it

was dark, the tide had gone out, and the skiff was about two floors below their exit point. One young man, Ernie Anderes, jumped down first and held the boat against the burned ship so everyone else could jump a little more safely. Then they headed back to Ketchikan.

“And when we got back to his house, excuse the language, all hell broke loose,” she said. “The Anderes had called all of our parents, and everybody was gathered there.”

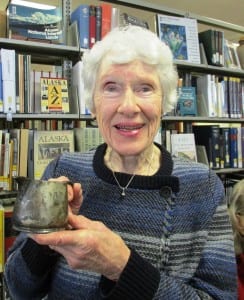

Aegerter said the young adventurers each got grounded for a couple of weeks, but they each had the consolation of a genuine souvenir from the Prince George. Aegerter’s was an inscribed metal cup, which she still has. She brought to the forum, and held it up for everyone to see.

The panelists talked about much more during the approximately one-hour forum. You can listen to the entire discussion, posted below.