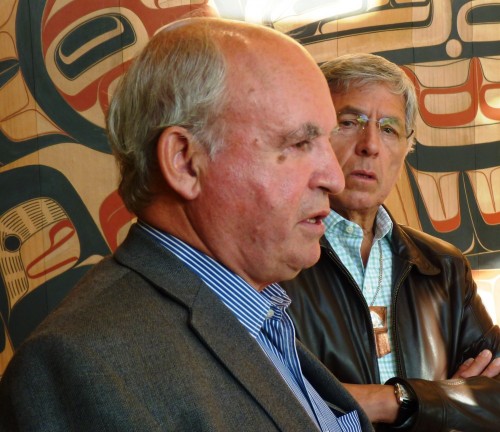

B.C. Minister of Mines Bill Bennett, left, discusses his trip up the Taku River with Lt. Gov. Byron Mallott in the Walter Soboleff Center lobby Aug. 24 in Juneau. (Photo by Ed Schoenfeld/CoastAlaska)

Tailings dams are one of the scariest parts of controversial British Columbia mines and mining projects.

They hold back water and waste rock left over from mining and milling ore. That includes rocks that need to be kept underwater so they don’t create rusty, acidic water. Tailings can also contain metals that are harmful to fish, wildlife and people.

Concern grew last year when the Mount Polley Mine dam breached in an eastern British Columbia. It sent billions of gallons of water, silt and rock into nearby waterways.

Critics of B.C. mines on transboundary rivers flowing into Alaska say such dams are unsafe and should no longer be allowed.

They cite a technical report released after the Polley incident that suggested waste rock be stored dry.

B.C. Minister of Mines Bill Bennett disagrees.

During this month’s visit to Southeast Alaska, he sat down with CoastAlaska News and discussed the tailings dam controversy.

Bennett said the Polley technical report has been misunderstood. He said dry storage is listed as one example of several available technologies to be considered by mine developers. Another is a well built tailings dam.

He quoted a letter from one of the report’s authors.

“Best available technology is not a single technology. There is a selection that has to take place that’s based on site-specific risk management process,” he said.

We asked him whether the Mount Polley accident was an example of a site-specific situation.

Bennett said the dam breach was caused by human error and a specific set of circumstances. But he didn’t rule out the possibility of a repeat.

“Mount Polley is not part of a pattern of bad behavior, as some folks have suggested,” Bennett said.

He said his ministry is working with mining industry engineers to improve standards. Existing mines are getting more inspections and other scrutiny. And new projects will face more restrictions.

“If a mine has not been constructed yet, they will absolutely have to comply with the new regulations,” Bennett said.

He said tailings dams will continue to be a part of mining in British Columbia. But it’s not the only approach.

“Dry-stack tailings will be incorporated in some of the new projects in B.C. I have no doubt,” he said.

He said his agency will spend more time scrutinizing tailings storage options.

“We want the detail. We want you to show us how you examined the relative merits of various ways of managing tailings,” Bennett said. “So, if you say to us, ‘Oh no, dry-stack doesn’t work for us,’ fair enough. But you have to prove to us that that is in fact the case. And cost cannot be the only driving factor.”

One of the criticisms of tailings dams is that there’s no guarantee they will last for hundreds, if not thousands, of years, protecting fish habitat.

Bennett said it’s a misperception that dams have to last forever.

“So, what typically happens over time, is those tailings storage facilities get capped with impervious material. A plan is made for dealing with water that runs over the site in the future. And those dams are not left to stand forever and ever, holding back water,” he said.

Other reports about Bennett’s Southeast Alaska visit include: