Ketchikan resident Sabra Simmonds spent almost two years living and working in Afghanistan. She recently made a presentation at the Ketchikan Public Library about her life in the Middle East. In the first part of a series, we look at day-to-day life.

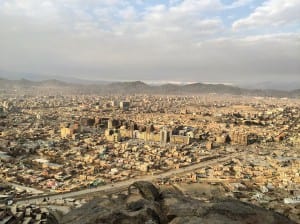

Simmonds lived in the capital city of Kabul, serving as communications advisor to the Afghan Minister of Agriculture. Simmonds shared her experiences and answered questions about life in Afghanistan. Joining, via Skype, was retired Lieutenant Colonel Khoshhal Sadat. Sadat served as General Stanley McCrystal and General David Petraeus’ Afghan liaison during the command of the International Security Assistance Force.

While Simmonds and Sadat provided information about the history of Afghanistan and the current political climate, much of the presentation focused on day to day living – what homes look like, the ease or difficulty of shopping, and even what it’s like to drive in a major Afghan city.

Simmonds began with a humorous, personal story. She and a friend were driving in Kabul when they saw an elderly man selling bags of goldfish out of the back of a wooden cart. It was another friend’s birthday, so they decided to buy a special gift. When they got home, they tried to transfer the fish into a bowl of fresh water.

“Afghanistan is a land-locked country. Not that goldfish are coming from the ocean, but we had no idea where they did come from. But we thought, ‘This will just be the most fantastic gift,’ but unfortunately the goldfish had seen better days. So we were trying to salvage them and give them a better habitat. I think they ended up dying, but we tried our best.”

Simmonds says she lived in a “normal house” and could come and go freely. She says Westerners living in compounds are not allowed to leave the area they are confined to.

“They have three barricades that it takes to enter. You need to get permission to enter. Afghans are not allowed inside unless under strict supervision. People sometimes call the US Embassy ‘Pyongyang.’ You don’t know what goes in and you don’t know what goes out.”

Simmonds says because she wasn’t in a compound, her experience was very different from those living in an embassy or military installation. She would exit her door directly into the streets of Kabul. Though she enjoyed many freedoms, Simmonds says, being a Westerner, she had to take precautions. One of those precautions is to have a safe room with a fortified, locking door. She did not.

“So this is our bathroom door, but it couldn’t shut. So if we were ever to be attacked or the Taliban were to storm, we really didn’t know what to do. But this sort of gave us that false sense of security that maybe everything will be alright.”

Simmonds says most bathrooms have bucket showers. A shower fixture is mounted on the wall, and a bucket placed beneath it to catch the water. She says there may be no electricity in the winter, and if there are outages, they can last up to six weeks. Simmonds says you learn to make do.

“As a woman we normally wear headscarves, so you don’t have to really worry because you’re covered all the time. So, hygiene sometimes…everyone smells the same…so it’s okay.”

Temperatures in Kabul in winter can get below freezing. Simmonds says most houses are made of mud or concrete and usually do not have insulation. She says a bukhari (boo-HAH-ree), a type of wood burning stove, is used to heat homes. Simmonds says if electricity is available, the bukhari is usually easy to light.

“But this is what happens when you don’t have electricity. You have headlamps. You put the headlamp on. You have to have your axe. You have to create little pieces of tinder. You just pray you don’t run out of matches and just hope it all works.”

Simmonds says dynamics inside and outside the home are very different.

“Inside you can be who you want to be…or who you are. Unless your neighbors are peering into your garden, you don’t have to worry about covering your hair. I walked into our courtyard in shorts. But as soon as you leave the safety of your house, things get a little bit different. However there’s still normal life going on.”

Simmonds says she would hike, paddle boat, and go for runs, though kept covered up. She says it isn’t common to see people exercising in Afghanistan.

Simmonds has driven in the busy streets of Kabul several times, but says it is rare to see women in the front seat of a car, let alone driving.

Her time was also spent working at the Ministry of Agriculture. She says she tested the country’s first solar powered car, monitored snow leopards, and worked with farmers to expand agricultural information.

Simmonds is back in the United States. She’s stopping in Ketchikan for a few weeks before heading to Washington, D.C. to work for an Afghan based consulting firm.