Workshops on the opioid crisis in Alaska were held in Ketchikan May 24th. The hour-and-a-half-long sessions provided an overview of the situation, how the crisis happened, and where the state can go from here.

Dr. Jay Butler, Chief Medical Officer for the Department of Health and Social Services and Dr. Tessa Walker Linderman, Nurse Consultant with the State of Alaska Office of Substance Misuse and Addiction Prevention, led the discussion.

Butler began with a history of opioids. He says drugs related to the opium poppy have been used for thousands of years to relieve pain and treat medical conditions. Butler says, early on, it was discovered that some people couldn’t control its use, and had what was referred to as “opium hunger.”

Butler says the real crisis began in the 1990s due, primarily to two factors. The first was the Food and Drug Administration’s approval of the synthetic drug OxyContin. Butler says the drug was heavily marketed, leading to misuse.

“Some 34,000 coupons for your free prescription starter kit were distributed. These were generally through primary care providers. But ‘If you have low back pain, you don’t have to live with that anymore’ is how it was sold. ‘This is a safe drug that’ll take it away, and here, you can get your first month’s supply for free.’”

Butler says the second reason was a change in the way pain is perceived. He says at that time, pain was viewed as a vital sign, and care providers worked to eliminate pain. Butler says pain is not a vital sign, it’s a symptom.

Dr. Jay Butler discusses the opioid crises at a workshop in Ketchikan (KRBD staff photo by Maria Dudzak).

“Vital signs are things like pulse, respiratory rate, temperature, blood pressure. And I would never say to you, ‘On a scale of one to ten, what’s your blood pressure today?’ Yet that’s how we perceived pain, and we did not really think about the way that pain is influenced by past experience as well as current experience in terms of how the brain processes the signals that come in.”

He says OxyContin was also marketed encouraging care providers to increase doses if pain persisted.

Butler says changes in agriculture also contributed to the problem. He says most opium used to enter the United States from countries like Afghanistan and Turkey, and it was much harder to obtain. Butler says about 10 years ago, changes in agricultural practices in Mexico made it easier to produce the opioid heroin.

“What changed about 10 years ago, is that heroin began coming into the country which was much more pure, much more plentiful, so the price dropped, and there was a ready market, because there were many people who became physically dependent or addicted to opioids.”

Butler says most heroin overdose deaths are due to the addition of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid. He says fentanyl can be produced at one-twentieth the cost of heroin. Butler says fentanyl is more concentrated and more dangerous.

“Interestingly (there is) not a lot of evidence that as a nation we have more people who are self-injecting drugs than we had five or even ten years ago. But what is being injected is increasingly fentanyl which is a much more deadly compound.”

Butler says most don’t know that they’re using drugs containing fentanyl, and counterfeit pills are commonly produced. He says anyone using street drugs is at greater risk of overdose.

“Anytime you’re using a street drug, it’s a game of Russian roulette. With fentanyl on the streets now, there are more bullets in the chamber.”

Butler provided statistics for the United States and Alaska. He says in 2017, about 100 Alaskans died of opioid overdoses. He says while there have been declines in overdoses due to prescription opioid use, fentanyl has caused an increase in deaths in those using street drugs.

“I’ve shown a lot of data, a lot of graphs and lines, but it’s also been said in public health, Data is people with the tears washed away.”

Linderman spoke about what is being done in Alaska to address the problem. She says community cafes were held statewide to identify challenges in various communities. Linderman shared some of the comments gathered.

“‘We never used to see ambulances going down to the docks. It happens all the time now. We all know what is happening, but nobody is talking about it.’ And this woman’s son overdosed after returning from fishing for the summer, so he had a period of abstinence and then, as Jay had mentioned, when people come back, they use at the same level that they had been and we see overdoses. So that’s what this story is.”

She shared a quote from an elder in Klawock.

“The sickness has come to our island, to our state. We’ve got to figure out how to stop this. We have got to communicate with each other, because if we don’t, our people will die.”

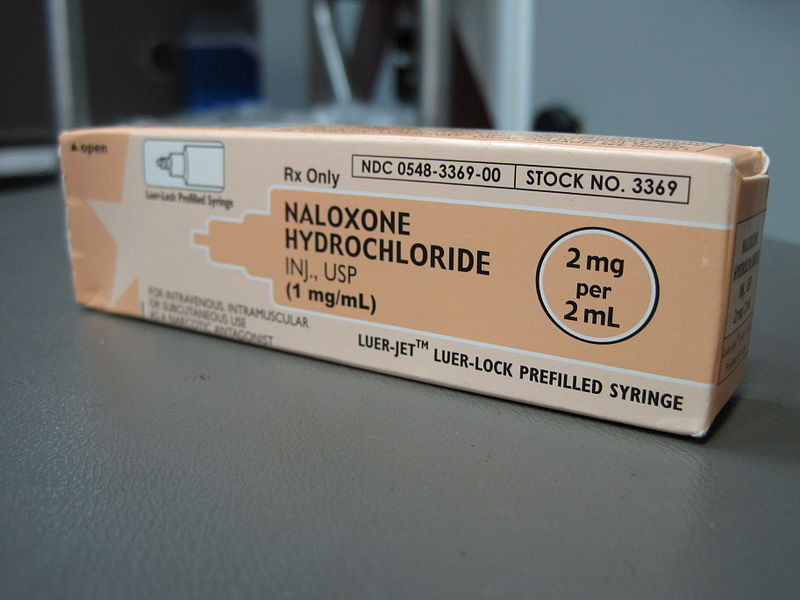

Linderman says the state is working on addressing the problem through a public health approach. A state-wide action plan is under development. She says programs include distribution of rescue kits to prevent overdose deaths, needle exchange programs, and checking illicit drugs for fentanyl using test strips.

Butler says recovery is challenging and abstinence is not effective. He says opioid addiction is a disease and should be treated through long-term management using alternative drugs such as methadone and sub Oxone. Butler says one barrier to recovery is the stigma attached to addiction.

“And that’s why it’s so important that we recognize that addiction is a health condition and that there are many people in recovery. And I can say as a health care provider, I didn’t see that. Because no one ever called me at 3 o’clock in the morning to tell me that they were still in recovery. I got called at 3 o’clock in the morning because of relapse.”

Butler says keys to helping end the opioid crisis include addressing supply and demand, providing long-term, medication-assistance treatment, reducing the stigma of addiction, and working together to find solutions.