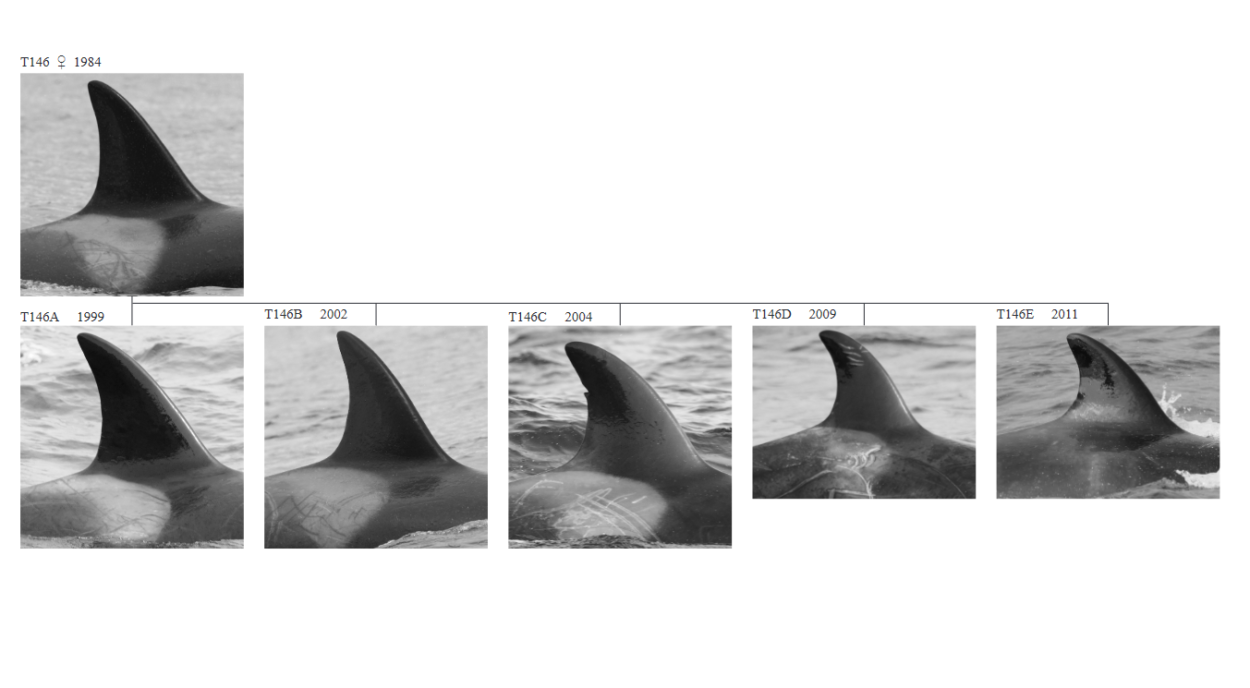

A page from the killer whale photo-identification catalog shows T146D’s dorsal fin. This fin helped a researcher identify Thursday’s beached orca. (Graphic: Fisheries and Oceans Canada).

Researchers have identified the killer whale that beached on Prince of Wales Island last week and then freed itself when the tide came in.

Its name is T146D. It may not roll off the tongue, but killer whale researcher Jared Towers says the name is important.

“It allows us to keep track of the whale after the stranding,” he said. “And that may be among the most important parts of identifying animals like this.”

The orca hasn’t been spotted since it freed itself on Thursday. Or at least, no one has seen it and identified it as T146D again. But Towers said the documentation matters.

He works for Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans and is part of a team of researchers called Bay Cetology. He led a team that compiled a photo-identification catalog of West Coast transient orcas, also known as Bigg’s killer whales.

“There’s over 300 of them,” he said. “They’re the ones that are typically seen from Alaska and further south, down to the Lower 48 off the west coast of North America.”

The man who identified the beached orca is Towers’ colleague, Gary Sutton. Sutton says the eye patch of the orca was fairly distinctive, alerting him that it might be T146D.

“It’s got a big kind of hook on the front and comes in,” he said. “It sets her apart from a lot of the rest (of the whales).”

But to be sure, he said he checked multiple photos of the orca against the catalog. Though he used feminine pronouns to refer to T146D, he said that the killer whale’s gender isn’t confirmed — it’s mostly a guess based on body shape. But he said they do know it’s 13 years old.

As for whether it will survive in the long-term, there are some good signs pointing that direction, said Sutton.

“I was fairly optimistic, because of the way it looked and the fact that there wasn’t a significant amount of blood and the tide pool below it,” he said. “…(It) seemed to be in good health.”

That said, contrary to some posts on social media, NOAA Fisheries spokesperson Julie Fair said they have not confirmed if the whale has rejoined its pod. But Towers said there’s a good track record of this species surviving the live-strandings.

Before this most recent stranding, he said five individuals from this population had been documented live-stranded over the last 20 years. All of them survived the initial stranding, he said, and four are still alive, as far as they know.

“They’ve all rejoined their families after stranding, and they’ve all gone on to survive and live normal, healthy lives,” he said. “And the only reason we know that is because their identities were documented when they were stranded, and their identities were further documented.”

Towers said there are several kinds of killer whales along the West Coast. But all the live-stranding events were Bigg’s killer whales, which he said like to hunt harbor seals in shallow waters.

“I don’t think anyone knows exactly when this whale stranded, or what the circumstances were,” he said. “But I would make a wager that there was harbor seal hunting as the motivating factor.”

Still, there’s a lot unknown about T146D — including exactly why it stranded. But because it’s been identified, there’s a good chance that the killer whale could be documented again, and researchers will know if it survived in the long-term, too.