The state ferry Malaspina sits in layup in Ward Cove near Ketchikan on May 10, 2020. DOT now admits it costs around $75,000 a month in moorage, utilities and insurance. (Eric Stone/KRBD)

The cost of keeping an idled Alaska ferry at the dock is nearly twice as much as publicly reported to the public and state lawmakers. That’s according to internal emails obtained by CoastAlaska in October, more than three months after they were first requested under state public records law.

First, the back story: The nearly 60-year-old ferry Malaspina was built the year JFK was assassinated. It’s part of the marine highway’s original three sister ships designed to connect coastal communities with each other and the Lower 48. But the blue and gold mainline ferry hasn’t carried passengers in almost two years.

Governor Mike Dunleavy’s administration didn’t want to invest in the overhaul of its original engines from 1963. Estimates of fixing the ship run upwards of $70 million for steel work, new engines and restoring its Coast Guard certificate which lapsed while the ship’s been laid up at Ward Cove, a private dock north of Ketchikan. Yet officials have apparently been unable to decide whether it would be best to scuttle, sale or donate the ship.

As recently as August 31, the marine highway’s general manager told CoastAlaska that plans to offload the vessel remain “on a hold.”

A floating barracks on the Horn of Africa, a $625,000 cash offer from UAE

There’s been talk of commercial interest. But for the first time email records show the nature of the inquiries. One firm says it wants the Malaspina for anti-piracy operations off the coast of Somalia.

“We would be using it as a platform for housing personnel over in the Middle East,” Jonathan McConnell, president of Meridian Global Consulting, a security firm, based in Mobile, Alabama.

The Malaspina has staterooms with more than 230 passenger bunks that he says could be outfitted as sleeping quarters for security contractors that patrol shipping lanes to deter attacks from pirates off coast of Somalia, he said.

He provided recent email chains between his firm and state officials show that more than a year has gone by since he first expressed interest. He last reached out in July 29 with no answer.

“We felt largely stonewalled by them,” McConnell told CoastAlaska this week. He says his firm is willing to pay fair market value — close to $1 million.

He added: “And our claims were not even entertained, it seemed like.”

Another prospective buyer in the United Arab Emirates, had made a cash offer via email for $625,000 for the Malaspina as-is, emails show.

Several prospective buyers have said the 408-foot ship has cash value. It could be sailed or towed on a temporary Coast Guard certificate to be repurposed or sold as scrap.

“There’s ample opportunities for use for that vessel,” McConnell said. “Laying it up and spending $40 grand a month for a layup is astronomical, frankly.”

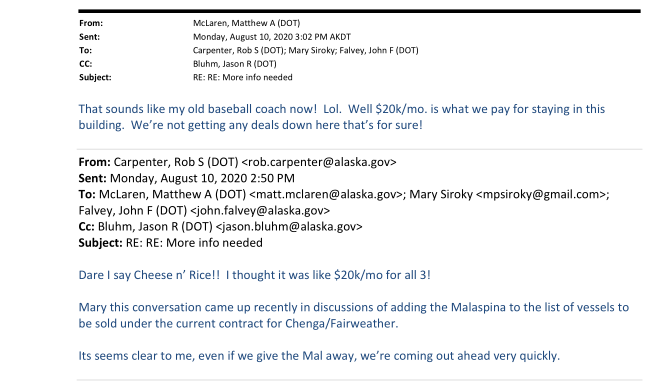

Internal emails show surprise at high cost of mooring and insurance

That was the view of many inside DOT as well. Internal emails — some of them completely redacted — show officials were surprised and frustrated with the expense of keeping the ship.

One email from Mary Siroky, a recently retired deputy commissioner, brought to light that the price of insuring the vessel made the true monthly cost of keeping the Malaspina closer to $75,000.

That was nearly twice the figure cited by the agency as the cost of mooring the ship at Ward Cove.

“Its (sic) seems clear to me, even if we give the Mal away, we’re coming out ahead very quickly,” DOT’s deputy commissioner Rob Carpenter wrote in an August 2020 email in response.

That was the apparent view of inside the Dunleavy administration which earlier this year tried to gift the ship to the Philippines.

A May 20 letter to the consul general in San Francisco made it clear it could go either to the foreign government or a private operator in the country.

But talks between Alaska and the Philippines apparently had been going on for some time. Internal emails show that a month before the official offer bearing the governor’s signature was sent, an email from DOT’s Rob Carpenter had inquired whether that deal with Manilla was still on.

Gov. Mike Dunleavy’s acting Chief of Staff Randy Ruaro replied the same day directing DOT to hold off.

“Do not do anything with the Malaspina,” Ruaro wrote in an email. “The Philippine Consul is interested and working on it on their end. The boat is 60 years old. We don’t need to rush to do something with it this month or possibly next. Please stand down from issuing anything that would dispose of the vessel until you hear from us to go forward. We will let you know.”

Ruaro told CoastAlaska this week that the deal fell through when the Philippine government learned it would cost more than $50 million to rehab as a passenger ship.

“They said that would be out of their price range for wanting the boat,” he said in a phone interview.

Malaspina stored long-term in $400,000 sole-source contract

But even afterward, the emails up to June 23 showed no evidence that efforts to dispose of the ship resumed. Or that further direction was offered from above. And that by that time the state had signed a contract with the Ward Cove Group to store the ship.

“With only a single interested party, the state processed a Single Source Procurement to authorize the award of a new contract to Ward Cove Group for $402,084 annually,” DOT wrote in an email to CoastAlaska in June.

The Dunleavy administration earlier this year the fleet’s newest ships — two fast ferries — were sold to a Spanish firm for service in the Mediterranean. Selling surplus ships had been a key recommendation of the governor’s task force giving advice on the future of the fleet.

Tom Barrett, the retired Coast Guard admiral tasked with chairing the working group, says it’s apparent the Malaspina remains a drain on state coffers.

“Sell it, or scrap it,” Barrett said in an interview. “But you just don’t want to keep holding it there indefinitely. Also you’ve got insurance, but it’s a risk factor, it’s an old ship and it’s tied up at a dock.”

DOT confirmed to CoastAlaska that the cost of insuring the Malaspina ferry was approximately $420,000 a year in fiscal year 2021 and says that figure would go up “slightly” in fiscal year 2022. Add the roughly than $450,000 the state is paying in mooring fees and electricity and the cost is nearly double than it has previously admitted.

Overseers of Alaska Marine Highway System concerned

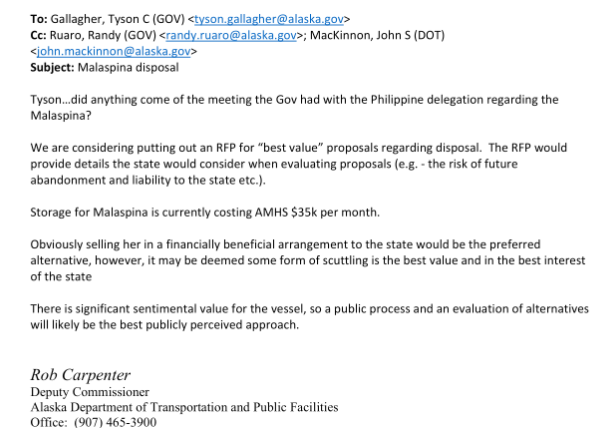

An April 21, 2021 email from DOT officials seeking guidance from Gov. Mike Dunleavy’s staff on how to proceed with the Malaspina. The governor’s office directed them to stand by while a deal to give away the ship to the Philippines was being worked out.

Those tasked with oversight of the ferry system say that’s a lot more than DOT even disclosed to lawmakers — which is particularly problematic given the marine highway system’s extremely tight budget that’s regularly a target of line-item vetoes.

“I’m very surprised to learn that the marine highway system is able to allocate this, this insurance cost across each vessel and that they never bothered to mention it to the legislature,” Sen. Jesse Kiehl, D-Juneau, told CoastAlaska. He’d been on the Senate Transportation Committee that had quizzed transportation officials on the carrying cost of idled vessels.

“We either need to get a federally funded project going and rehab this vessel to get it moving,” Kiehl said, “or we need to make a decision about disposing of the vessel as Alaskans.”

He added: “If the department’s not coming forward with all the facts, that ties the legislators’ hands of doing the job Alaskans sent us here to do.”

Ruaro, the governor’s chief of staff and a former senate aide to Sitka Republican Senator Bert Stedman, says he’s taken an interest in the Malaspina. He says he’ll be visiting Ketchikan to personally inspect the ship’s condition at Ward Cove.

He says he couldn’t immediately explain why there had been no answer to prospective buyers.

“I will step in and talk to DOT and we’ll make sure that any offers or expressions of interest are all reviewed and vetted for options,” Ruaro said.

Several emails from a DOT contractor reiterates there were several serious commercial offers for the Malaspina on the table, one from a Fiji ferry operator who had purchased similar vessels from B.C. Ferries.

Rob Carpenter, the deputy commissioner, underlined the scrutiny the agency was under as it faced tough decisions over the future of the ship.

“There is significant sentimental value for the vessel, so a public process and an evaluation of alternatives will likely be the best publicly perceived approach,” he wrote on April 21.

Since that email was sent, the idle and vacant Malaspina has cost the state of Alaska more than $400,000 in mooring fees, electricity and insurance to keep.