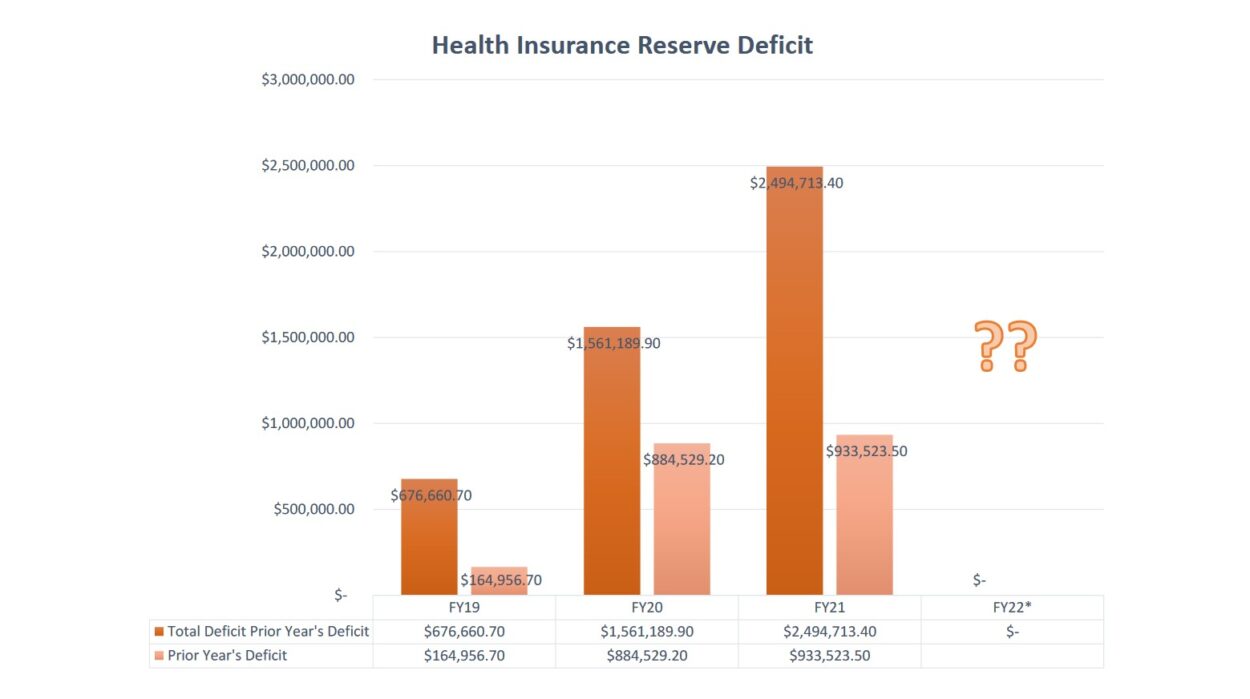

A slide from a presentation to Ketchikan’s school board showing escalating deficits in the district’s employee health insurance reserve fund. (Ketchikan Gateway Borough School District)

There’s a $2.5-million hole in Ketchikan school district employees’ health insurance fund. That’s the pot of money from which the district pays out claims as part of the school system’s self-insurance program. Though federal pandemic aid will cover a portion of the shortfall, school district officials say there are tough choices to be made in the not-too-distant future.

The way Ketchikan’s school district handles insurance is a little different from what might be seen at a small business. Instead of paying for a plan from a big insurance company, the school district is partially self-insured. That means it takes premiums, puts them in a pool, and uses that money to pay for medical expenses of its employees. For whopper bills over $150,000, it has a secondary provider that kicks in to insulate the school district against runaway expenses.

But for most of the last decade, school district business manager Katie Parrott recently told the school board, the insurance program has paid out more than it’s taken in.

“And the way that the district has kind of tried to deal with these deficits in more recent years is, we kind of do an end-of-the-year lump sum supplemental contribution to the program,” she told the board at its Oct. 13 meeting. It’s essentially an infusion of cash to keep the system whole.

But Parrott says the fund took a turn after a new teachers’ contract with the Ketchikan Education Association, or KEA — the largest union for faculty and staff. The 2018 contract cut teachers premiums by half — and that means less money going into the insurance fund.

“It created a new deficit on top of the existing smaller deficit. And at that time, it was projected that, ongoing, there would be about $522,000 that the district would need to make up somewhere in order to not feel the impact of that,” she said.

That’s another half-million a year. The school district went to the Ketchikan Gateway Borough to ask for local tax dollars to make up the difference, but the assembly shot down the request.

Over the next two years, the district put hundreds of thousands of dollars back into the account, combing through school district accounts looking for unspent funds at the end of the school year to keep the program afloat as the district searched for solutions.

Parrott says the union and the district drilled into the claims and found that a small group of employees was claiming much more than others. So they tried something new: programs to help employees address chronic, high-cost health issues like high blood pressure and diabetes. And it seemed to work.

“Now, whether or not it was directly as a result of those programs, it’s hard to tell, because those programs were so new. But we see that after a couple of years of really high claims, the program was shifting,” she said.

That was during the 2019-2020 school year. Then came COVID-19.

“After that,” she said, “our claims skyrocketed.”

With coronavirus-related claims coming hard and fast, a $700,000 deficit in mid-2019 ballooned to nearly $2.5 million by the end of last July.

“And so at this point, we have absolutely no choice whether or not we take action to address this liability,” Parrott told the board.

A little more than half of that is made up of COVID-19-related claims, she said. The school board voted unanimously on Oct. 13 to use the district’s final $1.4 million in federal relief from the American Rescue Plan Act to prop up its health insurance fund.

“That’s not going to take care of all of the deficit, but that’s going to knock out a good chunk so that maybe the remainder is more manageable for the district,” Parrott said.

But in the long term, Parrott says the district may have to take some painful steps.

She says there are essentially three options. One is to cut funding elsewhere to fill the gap but that would mean lost programs or activities. Another is to reduce health benefits. A third is to increase premiums. The latter two require agreement at the bargaining table

“It’s probably not realistic to target one specific long term strategy and only do that. I think it’s going to take a combination, but it’s definitely something that we need to have at the forefront of our coming budget cycle,” Parrott said.

The head of the Ketchikan’s teachers union, Gara Williams, says in an emailed statement that the current benefits were the product of long negotiations after district staff went without a contract for about 18 months.

Asking teachers, cooks, custodians, assistants and aides to either pay more for health care or get by with less “is going to be reminiscent of those contentious negotiations and generally be viewed negatively by our membership,” she said.

She says the union is also worried that cutbacks on health benefits could make it harder to fill an already high number of open positions.

The district has more than 350 full-time employees, including 157 certified teachers, according to a federal database. Contract negotiations for support staff and specialists like psychologists and speech pathologists get underway this spring.