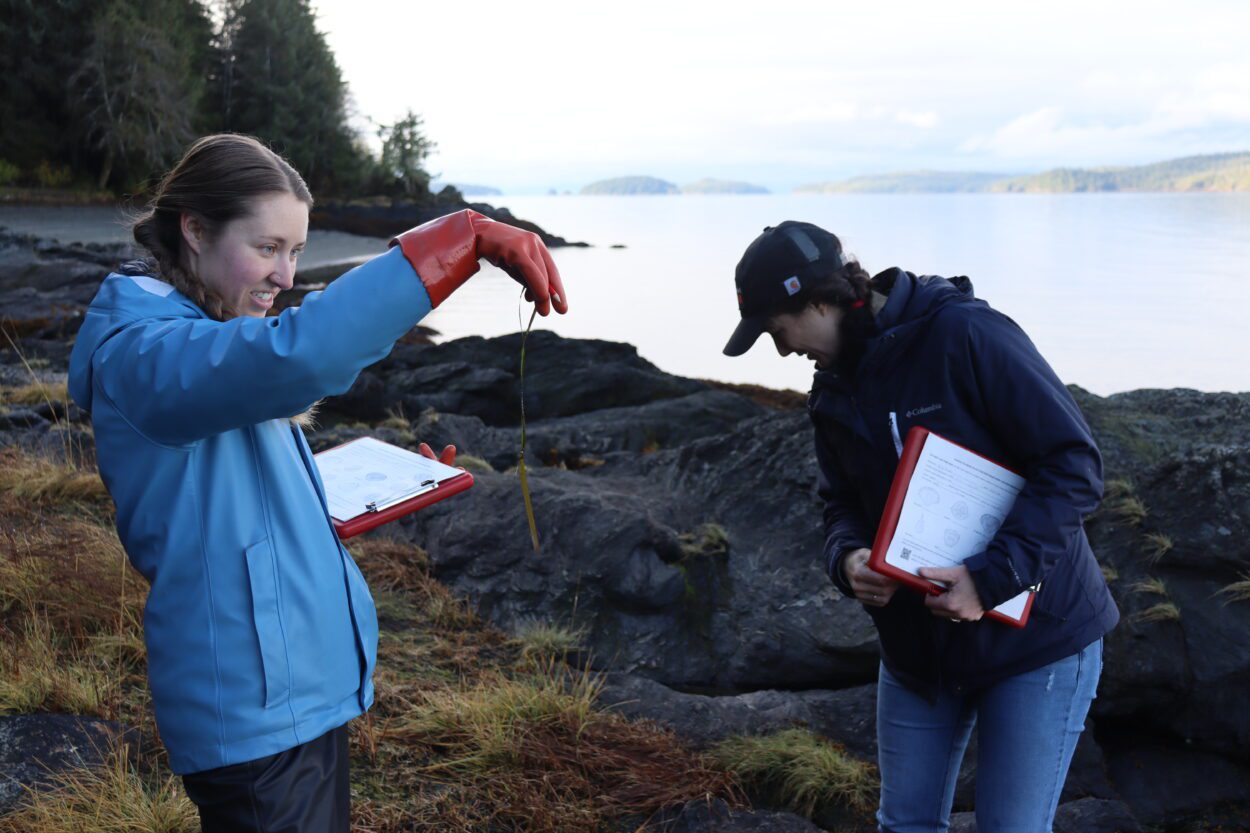

It was the first sunny morning in days, and two scientists donned in Xtratuf boots carefully strolled along a rocky, grassy shoreline. They were at Settlers Cove on the north end of the Tongass Highway. The duo are no strangers to flipping rocks and looking into puddles for carapaces, or crab shells.

Before long, they located the exoskeleton of a Dungeness crab, which is indigenous to Southeast and much of the West Coast. The find is somewhat of a relief to the group, who didn’t spot any invasive European green crabs that day.

But that isn’t always the case. Shells and live crabs were spotted to the north in Ketchikan this summer, and they’ve since been found on eight other beaches along the road system.

“Once they are in the ecosystem, they’re there, and they spread like wildfire,” said Ketchikan Indian Community Wildlife Biologist Emily Halsell. She leads the tribe’s European green crab management efforts, which include carapace walks.

“If we were able to remove them from the system, they would not be in five different continents. They would not be considered one of the top 100 invasive species in the entire world,” Halsell said. “Once they’re there, you’re not getting rid of them.”

European green crabs are Native to coastal Europe and north Africa, and were first detected on the North American east coast in the 1800s, and on the North American west coast in San Francisco Bay in the late 1980s. The crab isn’t always green but can be distinguished by its three bumps between the eyes and five spines on either side. It’s since migrated north by way of ocean currents.

The species officially reached Southeast Alaska, on Annette Island in 2022. That year, the Metlakatla Indian Community trapped about 800 European green crabs on the island.

And that’s about half of what they found in the few years that followed. But since April, that number has grown exponentially. The tribe has trapped over 40,000 European green crabs, sometimes up to 1,000 a day. The invasive has also been found in seven new locations on Annette Island, and in eight new locations across Southeast Alaska.

There’s a theory as to why the island’s seen an explosion of the pesky critters. It was an El Nino year, which is favorable for the crab larvae because it pushes warmer waters to shore. And female green crabs can lay up to 185,000 eggs at a time.

But it’s possible that not all green crab are the same. Ian Hudson is a fisheries biologist with the Metlakatla Indian Community. He says European green crabs in Alaska could differ from those found in British Columbia and Washington state.

“The combination of genetics that we have here is kind of like a super crab that is essentially adapting to the environments in Alaska and poses a huge threat,” Hudson said.

The invasive burrows into eelgrass beds, which destroy nurseries for Dungeness crabs, clams and juvenile salmon. Research also indicates that green crabs may be able to catch and kill baby salmon.

Hudson says the threats of European green crabs not only impact indigenous species, but Indigenous people. Annette Island is home to Metlakatla, the only Native reservation in Alaska, and Hudson says many residents harvest Dungeness crab and salmon for subsistence purposes.

“We’ve compared our bycatch data and our traps from year to year, and we have seen a decrease in Dungeness populations this year,” Hudson said. “We don’t know if that’s just an anomaly or if it’s conclusive, but we will continue to look at our data and have our data inform our choices and management for the future.”

And although green crabs have never been successfully eradicated anywhere, there are ways to manage them – like tracking their spread and trapping them. A new law in Connecticut allows harvested European crabs in the Atlantic to be sold in restaurants with little permitting.

Halsell, with the Ketchikan Indian Community, hopes to one day see management efforts like this in Alaska.

“There is no natural resource that people don’t enjoy to utilize that is way too abundant,” Halsell said. “So, we need to make it into something we can use.”

Scientists say European green crabs will continue to migrate north. As of now, they’ve been reported as far north as the southern end of Etolin Island, between Thorne Bay and Wrangell.

You can report invasive European green crabs on the Alaska Department of Fish and Game website. You can also report by dialing 1-877-INVASIV.

Hunter Morrison is a Report for America corps member for KRBD. Your donation to match our RFA grant helps keep him writing stories like this one. Please consider making a tax-deductible contribution.